In 2021 six members and partners of the RURALIZATION project developed innovative actions on emerging land topics. These actions covered a wide range of topics, from the conservation of hay meadows, to creating new visions for public farmland ; from exploring new ways to own farm buildings, to creating solidarity-based land access structures. A new RURALIZATION report cross-analyses the results of this field work and draws lessons on the processes of innovation they implement, guided by social and environmental concerns.

Ten actions on emerging land issues

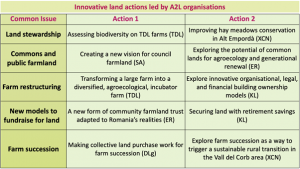

Over the course of eight months, De Landgenoten (DLg), Shared Assets (SA), Eco Ruralis (ER), Xarxa per a la Conservació de la Natura (XCN), Kulturland eG (KL), and Terre de Liens (TDL) – partners in RURALIZATION and members of the Access to Land Network – developed field-work around emerging land issues.

From the conservation of hay meadows, to creating new visions for public farmland, a total of ten pilot projects explored a wide range of topics. Each of them involved RURALIZATION partners developing concrete solutions, resources, partnerships to address relevant land issues in their respective countries.

This field work was analysed in a new report, which highlights both what is specific about each of the pilot actions, which tackle emerging issues in their specific contexts, and what is common to all these processes of innovation on land issues, guided by social and environmental concerns.

-> Read also our series of summarised “handouts” on each pilot action

Cross-analysing land innovation trajectories

Each partners’ field work was adapted to their local realities. However, the RURALIZATION approach consisted in adopting a shared methodology to document, analyse, and draw lessons learned as the pilot projects unfolded. Such a common analytical framework allowed performing cross-cutting comparisons of actions to understand their process, the resources used, the obstacles and levers encountered. This allowed drawing unique insights in the final report on the trajectories and specificities of social innovations on land. We learned that:

1. Innovations lie in the way issues are framed. The act of reframing can be an innovation in itself, by changing the perceptions of different stakeholders on the land issues addressed.

2. Innovations are implemented in an adverse context. Supporting agroecology and reforms in land governance requires navigating a system where this is not a mainstream view. Thus innovators must think strategically about how to build power to counterbalance more dominant narratives.

3. Innovations need to build legitimacy to “attract” different capitals. Legitimacy can be built in multiple ways (e.g. developing expertise, convening relevant parties, creating new partnerships…) and is necessary to mobilise social, political, financial, human, and natural capital to support innovative land actions.

4. Innovations change the way land is considered. New approaches developed by land organisations produce results that challenge dominant trends around land prices, environmental degradation, the perception of land as purely a financial asset, and the general decline in rural land-based economies. Thus, these innovations also have broader impacts on promoting generational renewal and rural regeneration.

How can we support further development of land innovations?

The report also critically looks at the conditions under which land organisations can benefit from action research processes such as those implemented in RURALIZATON. It shows that innovations follow logics of inspiration and adaptation to their local contexts rather than logics of direct transfer or top-down replication. To this end, action research methods can prove a powerful ally, for instance to formalise strategic assessments of the context. By encouraging the documentation of innovations processes, action research allows reviewing main steps, difficulties, and successes of projects and thus helps resolve issues and think strategically about achieving impact. Alliances with researchers however only represent one facet of the alliance needs and strategies of grassroots organisations. Unfolding these innovations also requires engagement with and support by public institutions, policymakers, citizens as well as farmers or land users/owners ready to engage in the direction they propose.

The report concludes with a number of recommendations to facilitate and upscale innovative land work. For instance, policymakers and funders should be sensitised to the fact that innovation processes can take time and require more flexible financing and project frameworks, as their paths are not linear and can require major adaptations in an adverse context. Furthermore, without in-depth regulatory changes, land markets and mainstream agricultural subsidy policies will continue to largely marginalise new entrants and agroecological farmers. In this context, innovations are likely to remain in “social bubbles” which only provide local solutions or solutions for a small group of users but do not solve the issue systematically. Finally, the report calls for building more spaces to hear voices and harness expertise and experience of innovations, which can provide direct information to policymakers on tried-and-true solutions for access to land.

Alice Martin-Prével

Fédération nationale Terre de Liens