Hope locates itself in the premises that we don’t know what will happen and that in the spaciousness of uncertainty is room to act. When you recognize uncertainty, you recognize that you may be able to influence the outcomes—you alone or you in concert with a few dozen or several million others. Hope is an embrace of the unknown and the unknowable, an alternative to the certainty of both optimists and pessimists. Optimists think it will all be fine without our involvement; pessimists take the opposite position; both excuse themselves from acting. [Hope] is the belief that what we do matters even though how and when it may matter, who and what it may impact, are not things we can know beforehand.

This passage, from Rebecca Solnit’s “Hope in the Dark” (p. xiv), is a good illustration of the current conundrum that European rural areas are facing. The status quo is clearly unsustainable; but the way out of it is not clear yet. How can rural changemakers act in this position, then? Which paths should they choose and on what basis?

The status quo is falling apart

The manifold rural decline in Europe has been obvious for many years now but it’s becoming increasingly serious nonetheless. A decline of both human and non-human species in the countryside continues: for instance, the abundance of common farmland birds fell by 27% between 1990 and 2019 (https://www.eea.europa.eu/ims/abundance-and-distribution-of-selected). At the same time, populations of animals exploited by humans in agriculture are on the rise (https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?title=Agricultural_production_-_livestock_and_meat)–and the EU is still promoting their consumption despite clear scientific evidence of its unsustainability and mounting ethical consciousness pointing in the other direction (https://euobserver.com/green-economy/151495). The level of nitrogen runoff stopped decreasing, as it did in 2000-2015, and remains unacceptably high (https://www.eea.europa.eu/airs/2018/natural-capital/agricultural-land-nitrogen-balance); in the summer of 2022, forest fires resulted in a 15-year record in wildfire emissions (https://atmosphere.copernicus.eu/europes-summer-wildfire-emissions-highest-15-years); and last but not least, the rural decline coincides with the rise of conservative populism in Europe, as those who feel left behind more often vote for anti-EU parties (https://www.dw.com/en/rural-eu-citizens-more-anti-european-and-anti-democratic-study/a-56053700).

These (selected) symptoms of a multifaceted rural decline are not just minor obstacles on an otherwise right track; they are deeply embedded in the 20th-century logic of agriculture and rural development. As a sector, agriculture has been subject to the capitalist logic of constant accumulation (including land accumulation), increasing efficiency by reducing–or rather shifting–costs, domination over nature by means of technology, and extracting as much ‘value’ from people and the environment as possible. Similarly, rural development has been associated with the pursuit of economic growth, a (race-to-the-bottom) competition with between rural regions, and the model of homo oeconomicus–an insatiable and ‘rational’ individual pursuing narrowly-defined profit at the expense of broader community, environment and future generations. In fact, preliminary results of the assessment of national CAP strategic plans in Work Package 7 of RURALIZATON show that the same model is reproduced by CAP measures addressing generational renewal, as they are (1) almost exclusively based on financial measures, (2) assuming a model of market-oriented agriculture with high investments, productivity, profits and low costs, (3) supporting mostly individual, highly competitive and business-oriented farm managers, and (4) prioritize short-term goals of keeping the agricultural sector competitive over long-term goals of sustainability. The result is obvious: some farmers win but those who lose the competition pay the price. Other farmers are pushed out of the market, jobs and rural communities are disappearing, the environment becomes further degraded and non-human animals continue being treated as metabolic work suppliers rather than sentient beings.

Weak signals as the way out of the crisis

Given how far this model is from the idea of sustainability, it seems crucial for rural areas to look for thriving futures in radically alternative trajectories. Here the insights from the Work Package 4 of RURALIZATION are informative. As part of the trend analysis in this package, we studied three types of trends related to EU’s rural areas: megatrends, trends and, what is especially relevant here, weak signals. Weak signals are, in simple words, phenomena which are not yet significant or widespread–in contrast to trends, or especially megatrends–but can become such in the future. It is especially important for strategic planning to take heed of weak signals because although they are not yet manifested, they might have a significant potential to bring about deep, systemic changes.

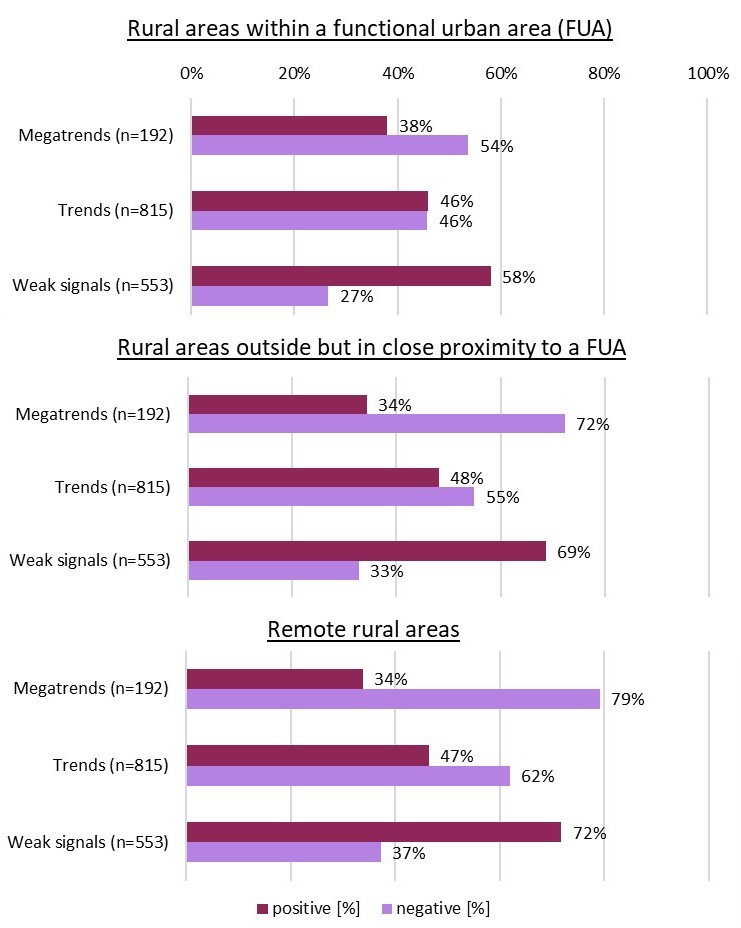

Interestingly, in Work Package 4 we found out that the potential benefits of weak signals are not distributed equally between all rural areas. While all rural areas start from a difficult position–megatrends and trends have more negative than positive consequences in them–the severity of impacts is different in rural areas within Functional Urban Areas (FUAs), rural areas in proximity to FUAs and remote rural areas (Fig. 1). On the hand, the further from the city, the more negative the impacts of broader megatrends and trends are. On the other, however, the further from the city, the more positive the impacts of weak signals also are. In other words, remote rural areas are suffering even more from the global megatrends and trends but also have more possibilities to benefit from weak signals than rural areas located closer to cities.

Fig. 1. Trends with identified impacts on rural areas by trend type, % of all trend observations

What it means in practice, is that rural areas (especially remote) should stop trying to make the future look like the past. The challenge ahead lies in an urgent, yet careful, assessment of weak signals that could offer a radically different and promising development trajectory. This approach is of course difficult since politicians tend to stay on the safe side rather than risk their careers by making a mistake. The existing systems around food or land-use planning also have significant inertia which makes it difficult to change them rapidly. And yet this is exactly what we should expect from decision-makers today, and what we should be willing to do ourselves: be courageous in abandoning the business-as-usual and picking these weak signals that can help us jump into a thriving future. A future that is not clear yet but wherein hope lies.

PS. RURALIZATION identified quite a few of such weak signals and even trends–e.g. ‘alternative food systems’, ‘care services’, ‘degrowth’, ‘food sovereignty’, ‘local paradigm’, ‘social enterprises and entrepreneurs’–which can be used as building blocks for desired alternative futures (see https://ruraltrends.eu for more details, a full report and convenient trend cards). Feel free to use them!